I imagine many of you have heard of “design thinking,” probably in the context of innovation, product and service creation, or solving complex problems. But what do we mean when we say “thinking like a designer”? Who does it involve, what does it imply, and how does it actually work?

When we hear the word “designer,” our thoughts immediately go to creators (Giò Ponti, Giovanni Pintori, Ettore Sottsass, Aldo Rossi, Philippe Starck…) and companies producing iconic “design objects” (Alessi, Olivetti, Kartell…) that combine a specific everyday function (coffee makers, typewriters, cups…) with the beauty of form and the uniqueness of small works of art. These are industrially produced, so they are accessible to many, not unique pieces confined to a museum. Perhaps architects are partly to blame for limiting the term in this sense, almost as if to identify “minor architects,” not quite on the same level as their colleagues who design large-scale works.

In fact, in English the verb “to design” simply means “to plan or create with a clear purpose in mind.” A “designer” is someone who designs (creates or builds) something for a reason and with a goal. “Design” therefore becomes the way in which that something makes sense, its nature directed toward a purpose for someone. It may be more or less (subjectively) aesthetically pleasing, but beauty is not necessarily part of design.

We can then say that “thinking like a designer means creating something that has meaning for someone.” It is worth pausing for a moment on the word “meaning,” because it is very important, and not only in this context.

Giving “meaning” to a linguistic expression means relating it, through associations, to an intentional object made of psychic experiences—both personal and collective (Husserl). The meaning (or “sense”) of something is the “way it is presented to us,” that is, the vast network of lived experience (religious practices and beliefs, attitudes and behaviors, cultural customs) in which it is immersed. With our rational thought and imagination, we have continually built and elaborated these “webs of significance” around us, as described by the great anthropologist Clifford Geertz.

Thinking like a designer has become a methodological approach, a way of thinking, and an attitude—centered first and foremost on a deep understanding of the networks of meaning in which the people we are designing for live.

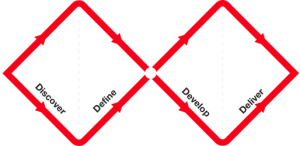

Its most rigorous and systematic codification comes from the Design Council. Initially, it was simply the “double diamond” (in this case, diamond is the suit of diamonds in a deck of cards, with the gemstone):

This work by the Design Council is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

The diagram reminds us of the fundamental phases of any innovative development:

- Discover the needs, empathically. The desires, gaps, frustrations, and pain points of those whose lives we want to positively impact by developing something (a product or service).

- Define what we want to do, identifying the beneficiaries and translating those needs, desires, and sought-after meanings into a specific, practical, and manageable challenge.

- Develop one or more responses to the challenge, inventing something and creating it in a simple, economical, and rough form (a “prototype”) that can be presented to the beneficiaries, to test the idea or concept and ask them if it “works” or if we are on the right track.

- Deliver something to the beneficiaries we identified, in the best, most careful, and respectful way, making ourselves available to improve it based on their experience and feedback.

The graphic form is intentional. Each diamond consists of two diverging arrows followed by two converging arrows, highlighting that the different phases involve different ways of thinking (divergent and convergent), which must remain completely separate. During the problem discovery and ideation phases, we must give total freedom to empathy, creativity, and imagination, which are amplified in collective contexts, without constraining them with judgment or practicality. These aspects come later, when identifying feasible and practical challenges (in terms of resources, potential, economic conditions, and market) and when creating and delivering effective combinations of products and services.

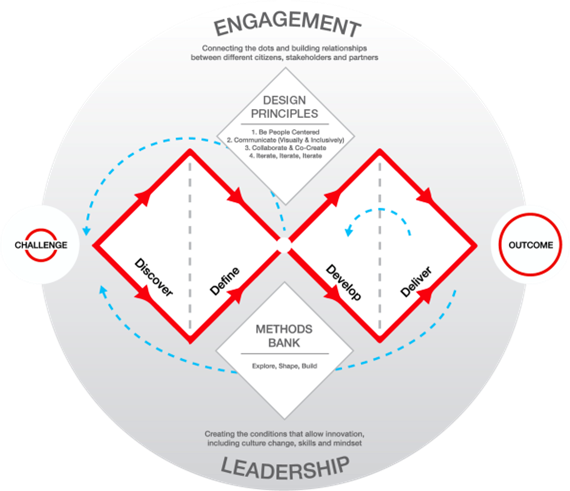

Over the years, and with the accumulation of experiences and shared practices, the Design Council has enriched the double diamond, recognizing its central role in every innovative process. It is also referred to under a new name, the “Framework for Innovation,” meaning a framework or discipline for innovation.

This work by the Design Council is licensed under a CC BY 4.0 license.

Beyond the explicit emphasis that the process starts from a challenge and arrives at an outcome, there are some important developments:

- The establishment of a series of fundamental principles and essential values that guide the design process:

- Human-Centeredness

- Communication (inclusive and visual)

- Collaboration and co-creation, the collective essence of the process

- Continuous iteration, represented by dotted arrows pointing in various directions, meaning the willingness at any moment to revisit what has been done and return to earlier phases

- The need to use a set of tested, shared, and validated methodologies, especially facilitation techniques, that ensure participation and the emergence of collective intelligence

- The importance of connections for engaging a variety of stakeholders

- The fundamental role of leadership, understood as “the capacity of a community to shape its own future” (Peter Senge), and therefore the use of participation to collectively create the conditions that make innovation possible

This is the deep nature of design thinking: a collective sensemaking process to tackle challenges and create solutions that improve someone’s life. Think of navigating the double diamond as a kind of mental “breathing,” divergent and convergent, that remains constant even if its pace changes depending on the conditions

If what we have said so far seems obvious and intuitive, either you are an extraordinary optimist or you have little contact with companies that should “breathe” in this way. Unfortunately, design thinking is often neglected in everyday business practice. Why?

Because a mindset focused on the company, its financial results, and the product, what it can do well and profitably, dominates. Companies fail because they do not invest in real innovation, and they get lost developing “things” that serve no one and that no one desires.

Management’s contact with the living, personal reality of customers is limited to occasional, well-orchestrated promotional demonstrations and guided interviews designed to confirm what they think they know, to hear only what they want to hear.

Thinking like a designer is not easy in organizations that aim to “convince” the customer rather than “captivate” them with the delight of an offer that meets their needs and desires.

We also need to understand both deeply, because we can find different solutions to a need, often the painful necessity of something we lack for our well-being. But we can also desire something we do not need, such as a gourmet treat or an inviting dessert when we are already full, or a new T-shirt when our wardrobe already contains hundreds.

This is why “thinking like a designer” gains new and unexpected dimensions and reaches unexplored territories. It forces us not only to observe empathetically the people we want to serve, but also to see them in their complex individuality and in their interactions with their world. It reminds us of Geertz and the things that have meaning in the psychological, social, and cultural context in which we live.

Henry Ford, regarding the Model T, famously said, “You can have it in any color you want, as long as it is black.” He and his successors treated consumers, at best, as purely rational beings who chose based on price and functionality, potentially “manipulable” with needs created through persuasive techniques.

Introducing anthropological elements into the development of innovative products was a true Copernican revolution, a fundamental paradigm shift. It shifted attention to the creation of meaning, not products, sweeping away everything else. All organizations, not only commercial ones, must reverse their perspective and equip themselves with tools suitable for decoding new languages and understanding new structures. To return to Henry Ford, we can say, simply, that cars must be produced in the colors that, in different cultural contexts, carry the most relevant connotations so that the customer can “feel” what they want.

Recently, the magazine DOMUS published an article titled Berlin Might Never be The Same Because of a New Urban Highway, drawing attention to the dangerous trajectory of a city like Berlin. A massive urban project risks “seeing the end of its exceptionalism,” as writer Vincenzo Latronico stated, who is also the author of the important coming-of-age novel and essay La Chiave di Berlino (Einaudi, 2023), particularly relevant for anyone who has loved this incredible city.

We are talking about the completion of the last section of the city highway “A100,” fully funded and approved by various political forces in government. Supporters argue that the project would have a positive impact for all stakeholders—that is, everyone, even marginally affected by the project—and could drive, with the introduction of new technologies, an extraordinary and ecologically sustainable evolution of urban transport. In other words, it would not be the social devastation of gentrification, the forced eviction of residents in working-class neighborhoods to renovate housing for high-end buyers, which affected some areas of London.

However, the local population mobilized, bringing tens of thousands of people to peacefully protest. Not only the usual squatters, students with limited funds, and lovers of extreme techno clubs, but a cross-section of startuppers, small shop and café owners, families, and casual coffee enthusiasts, passionate about cultural and ethnic diversity, whose collective interest is the defense of the “web of meanings” that the A100 would destroy. Latronico continues that Berlin’s exceptionalism also means very low costs of living and extremely high tolerance. This exceptionalism was built in part through the organic development of a network of techno clubs over the years, which cannot simply be relocated elsewhere. Even underground culture wants and can play an important role in this struggle to protect the meaning of something collective, something we feel part of, without necessarily closing ourselves off in an identity fence, and something we would like to invite others to experience and share.

Thinking like a designer, therefore, is much more than inventing successful products and services. It is a living, engaged, open, and respectful attention to the world of others. It is an invitation, a discipline, and a strategy to do the “right things.” The complex and unpredictable world in which we live often forces us to make choices in paradoxical situations, but it is precisely in the acceptance of paradox, of apparently irreconcilable opposites, that the inexhaustible source of collective creativity lies.

One last point: if the pursuit of “meaning” is the fundamental element of any activity that aims to create something for someone, we must not neglect its centrality regarding the activity itself and those involved. Work must start from an awareness of its purpose, the deep meaning of our work, the ultimate goal of the effort we put into what we do, and the greater good we want to contribute to.

Organizations and companies are places of value creation, fueled and justified by the collective intelligence of the people who are part of them. A serious and open reflection, and a shared understanding of purpose as a group, is the best starting point to truly think like designers, beginning with ourselves in the empathetic exploration of the webs of meaning of those we dedicate our work to.